In a country where trade competitiveness depends on the efficient transportation of minerals, agricultural products, and manufactured goods to ports, the rail system is not just a transport backbone; it is also a strategic asset.

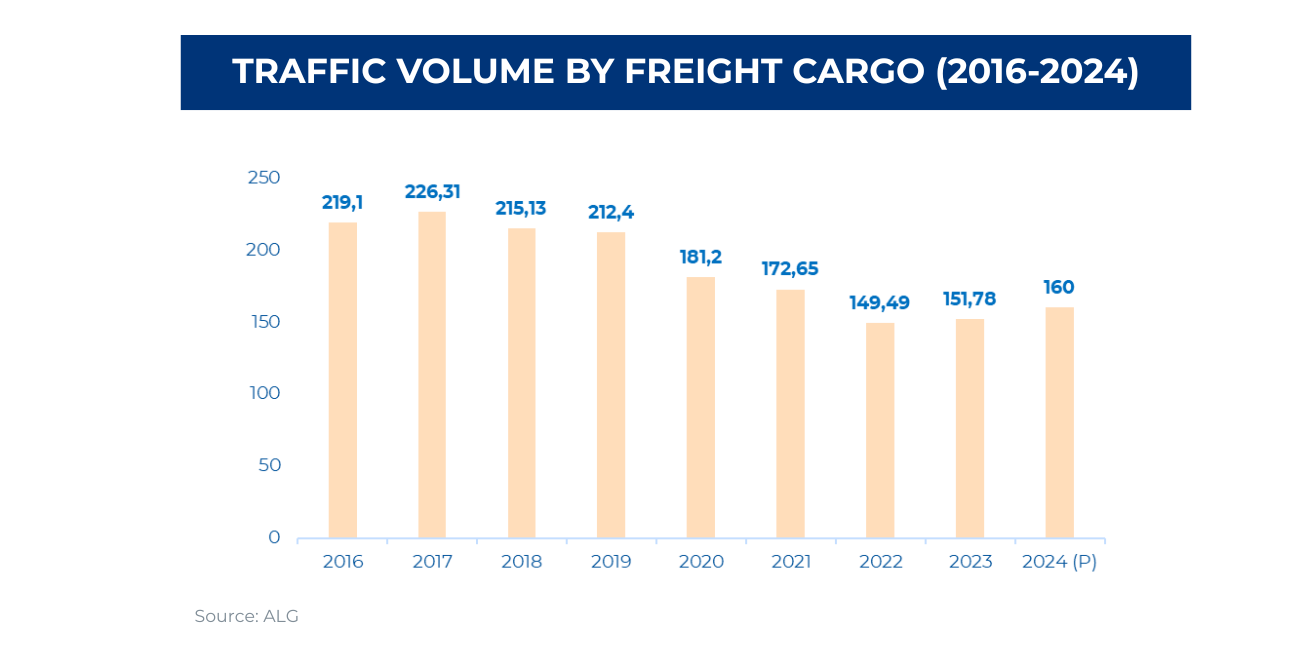

Rail freight transport in South Africa has been in decline for years. Peak demand was reached in 2017 at 226.3 million tons, but by 2022, volumes had fallen by 34% to a historic low of 149.5 million tons. This decline is primarily due to deteriorating network performance in recent years, characterized by delays, poor maintenance, equipment shortages, cable theft, and vandalism. These issues have impacted the system's reliability and capacity. Although Transnet Freight Rail predicted a recovery to 160 million tons by 2024, the network was still operating well below capacity. Therefore, South Africa's rail sector is now entering a new phase of restructuring.

After decades of state monopoly under Transnet, the government has begun to liberalize the railway sector, allowing private operators to participate in the freight network. The reform aims to revitalize the system, improve efficiency, and increase cargo capacity to reduce pressure on the country’s road infrastructure.

In recent years, both exporters and manufacturers have been affected by the lack of capacity, forcing them to divert part of their cargo to road transport. Companies such as Kumba Iron Ore and Thungela have had to reduce their production due to a lack of trains to transport their ore to the port. With the new reforms, they now have access to new opportunities, including more export contracts, lower costs compared to trucks, and greater reliability.

Furthermore, the structural change means that carriers, 3PLs, and multimodal operators can move away from being passive customers of a monopoly and instead design integrated supply chains that combine rail, road, and port capacity. Until now, many of them had been forced to transport goods by road due to the collapse of rail volume.

Ports also have been affected; in Durban and Richards Bay, the lack of reliable railway service has significantly extended export cargo wait times. In Richards Bay, over 300,000 trucks a year are now entering the port as rail failures force bulk minerals onto road transport, creating queues of trucks stretching along major access roads such as the N2.

The decision to liberalize South Africa’s freight railway market is not only an institutional change, but a transformation that radiates across the entire logistics ecosystem. The impacts vary depending on the stakeholder, from state-owned entities to private operators, exporters, manufacturers, and logistics operators.

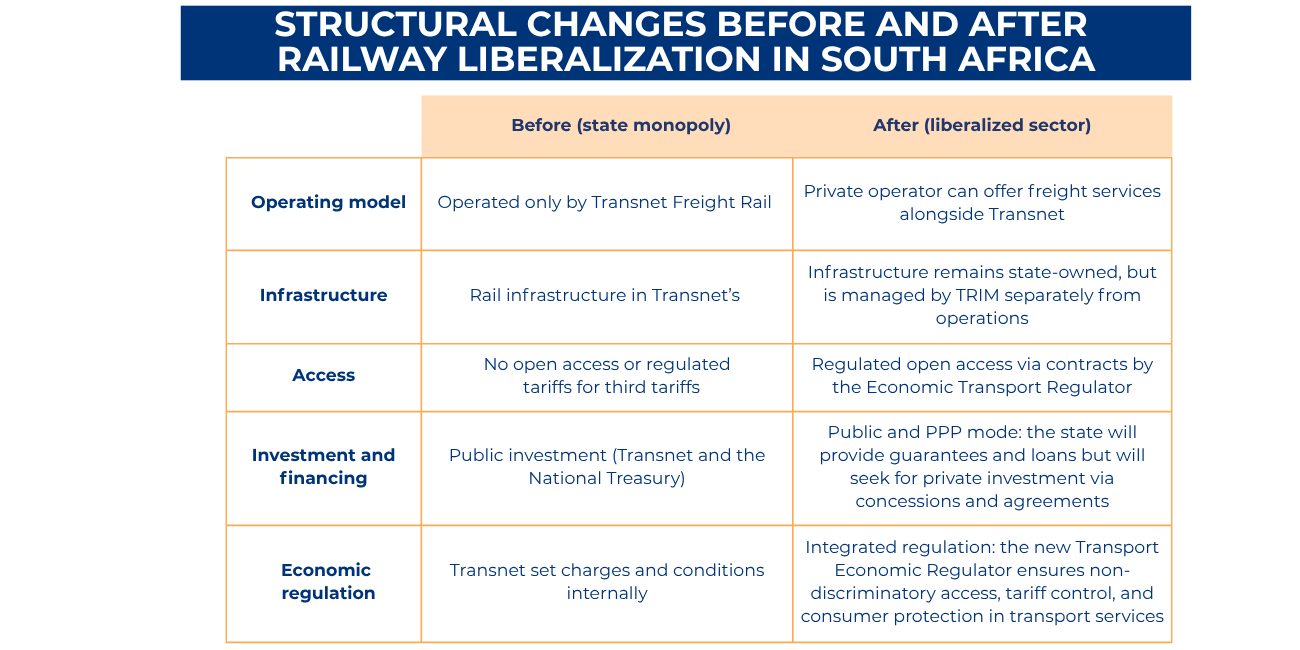

The initial railway setup in the South African railway sector has been vertically integrated, with railway infrastructure ownership, management, and operation all lying within public entities. Until 2023, this mandate was executed by Transnet Freight Rail (TFR) for service operation and infrastructure. The liberalization of the railway sector has led to a structural reform: the separation of infrastructure management from operational activities:

- Transnet Rail Infrastructure Manager (TRIM) oversees the country’s rail network. It is responsible for track maintenance, the allocation of train paths (slots), and the publication of the Network Statement, which sets out the terms of access for operators

- TFR, which now competes as one operator among many

At the same time, South Africa, to consolidate the path towards open access, enacted the 2024 Economic Regulation of Transport Act, creating an independent Economic Transport Regulator. This body is responsible for preventing monopolistic practices, ensuring competition, and regulating tariffs.

In terms of financing, to sustain the estimated freight network capacity the AfDB released the first tranche of a 1Bn USD loan to support Transnet's activities. Additionally, plans are in place for a dedicated LeaseCo to rent locomotives and wagons to new entrants, further emphasizing the shift towards a hybrid model.

How structural reform reshapes supply chains and logistics strategies

These structural reforms will revitalize the South African rail system. As a result, service efficiency is expected to improve as customers gain bargaining power, forcing operators to ensure reliability. With the entry of new operators and improved infrastructure, South Africa has the potential to increase demand for freight transport, thereby stimulating growth in imports and exports.

With this in mind, the government has set an ambitious target to add 20 million tons per year from 2026/27 onwards, with the aim of reaching 250 million tons by 2029. Exporters of coal, iron ore, manganese, and agricultural products have previously experienced frustration due to bottlenecks, but will now have more options, competition and predictability when transporting their goods. This will enable them to overcome supply chain constraints and become more competitive in global markets.

Recently, in August 2025, the Ministry of Transport announced the eleven private operators (out of 25) that had met the criteria and were pre-selected to access 41 routes and six key rail corridors. These corridors cover the transport of both bulk and containerized freight (coal, iron ore, chromium, manganese, sugar, and fuel). The new operators will sign access agreements with Transnet, granting them slots to operate trains for periods ranging from one to ten years. Among them are Grindrod, which is involved in logistics, and mining groups such as Menar, who are seeking to secure the transportation of their production.

With liberalization, stakeholders will have the opportunity to transport goods that were previously beyond their reach, as the main objective is to increase Transnet's capacity and improve the system.

For multimodal logistics, this presents both an opportunity and a challenge. Until now, freight forwarders and third-party logistics (3PL) providers were customers of a monopoly led by TFR. They suffered cancellations, had no bargaining power, and resorted to road transport to make up the shortfall. Their role was passive:

- Purchase limited capacity on TFR trains.

- Adapt to cancellations and delays without being able to negotiate.

- Compensate for rail deficiencies with more road transport.

This meant that logistics agents did not have the means to guarantee reliability to exporters or optimize multimodal chains.

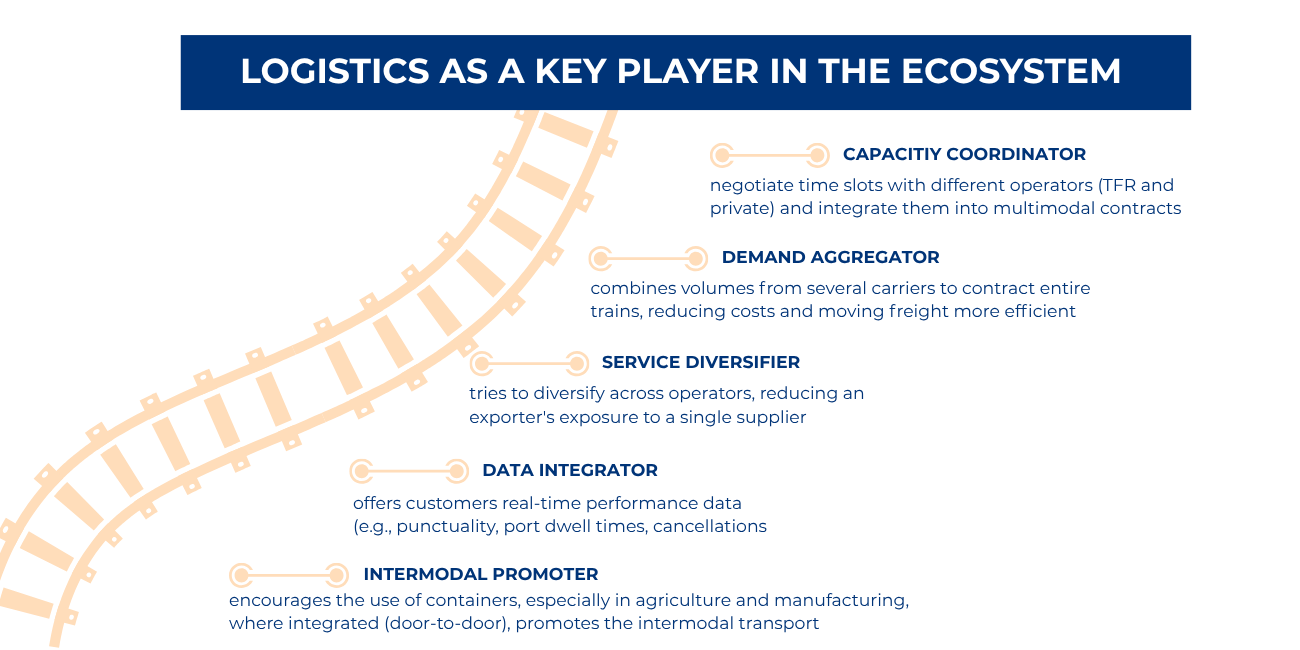

However, with the entry of private companies and the separation between TRIM (infrastructure) and TFR (operators), logistics has become a key player in the ecosystem with new roles to perform:

South Africa has the potential to reshape its logistics landscape, with the sector helping to develop dry ports and intermodal terminals in the interior’s country, as well as services to improve the lost reliability of the railways. Beyond infrastructure, logistics providers can also develop the digitization of the system, providing platforms for booking time slots and offering end-to-end visibility across the supply chain.

Similar cases occurred in Europe following the free access directive in the 2000s, when logistics operators promoted the growth of intermodal transport, creating block trains between inland terminals and ports such as Hamburg and Rotterdam. In Australia, with the Australian Rail Track Corporation (ARTC) managing open access, carriers organized intermodal trains between Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth, signing stable contracts with large shippers and reducing pressure on the roads. According to the World Bank’s PPIAF Railway Reform Toolkit – Case Study: ARTC, the results were tangible between 1998 and 2004, the time lost to temporary speed restrictions on the Sydney–Brisbane corridor fell by 60%, while overall transit times on key intermodal routes improved by around 15%.

In short, South Africa's liberalization is a catalyst for logistics. Freight forwarders and third-party logistics providers (3PLs) can bridge the gap between exporters and operators, accelerate the recovery of rail volumes and ensure rail ceases to be a bottleneck, thus restoring its competitive advantage.

In this context, ALG has relied on a one-and-a-half-year study aimed at revitalizing the transport industry and encouraging the shift from road to rail in Africa.