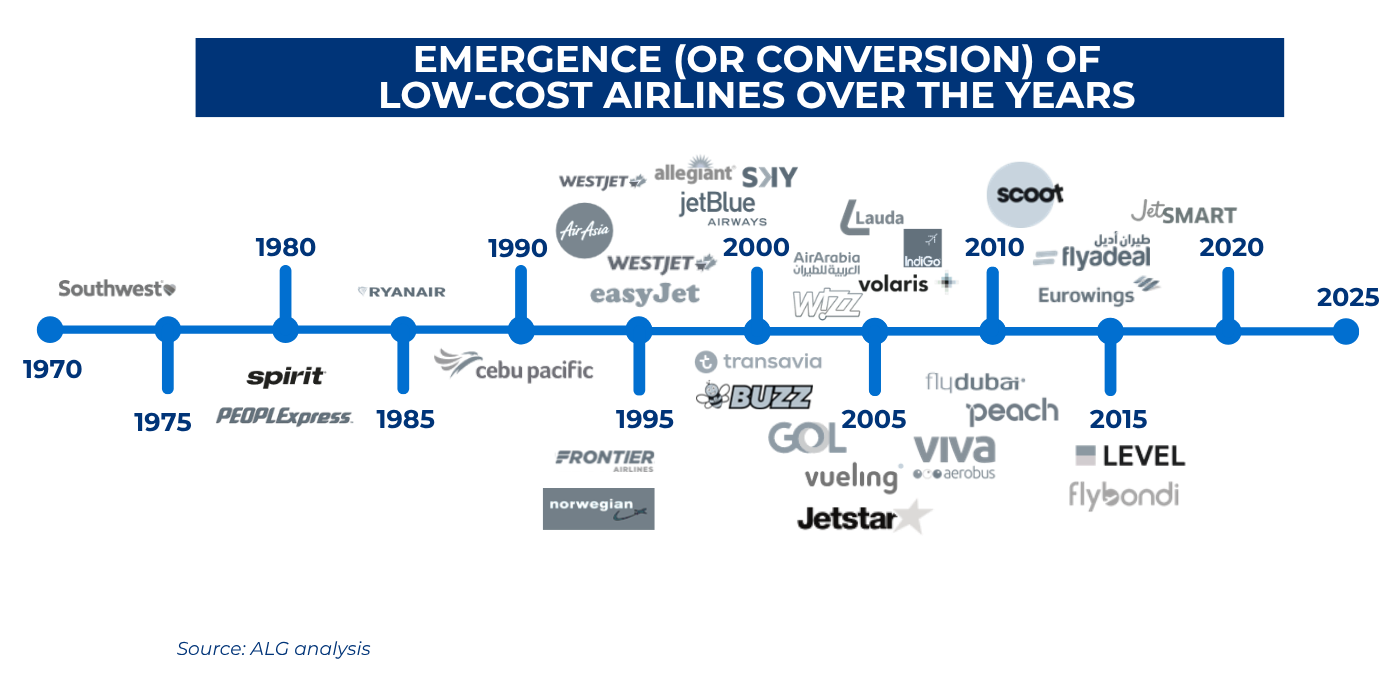

While their origins can be traced back to earlier decades, low-cost carriers (LCC) rose to popularity in the 1990s and 2000s in the US and Europe. LCCs appeared in the United States in the 1970s following the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, which eliminated federal control over market access, routes, and fares, and set the ground for the appearance of new business models.

Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA) was among the first LCCs in the United States, achieving rapid growth through the operation of routes within California, as intra-state services where not regulated. Subsequently, Southwest Airlines, strongly inspired by PSA and benefiting from the deregulation of air traffic in the US, took the low-cost concept to its highest expression.

Southwest began operations in 1971 with services between Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio (intra-state services were exempt from federal regulation). The airline had a fleet of three Boeing 737-200 aircraft, and offered lower fares than its competitors. It subsequently extended its routes to other cities in the state and, following the deregulation of airlines in the US in 1978–1979, began flying to neighboring states. Since then, it has continued to grow, and by 1990, it had established itself as a pioneering airline, operating across much of the United States with its distinctive business model: many flights to few destinations and using only one aircraft model since its inception. In this way, Southwest Airlines became a benchmark and served as a model for other companies in different markets, especially in Europe.

Similar to what happened in the United States, the rise of LCCs in Europe came after the liberalization and deregulation of the market in the 1990s, which created a single market that allowed airlines from member states to operate services within (and to/from) any country in the European Union. Companies such as Ryanair and Easyjet took advantage of this new reality and spearheaded the LCC model explosion in Europe.

The deregulation of the European aviation market marked the beginning of its major expansion: in 1998, Ryanair acquired 45 new Boeing 737-800s, and in 2000, it launched its own direct sales website, further reducing costs by eliminating intermediaries. From then on, the company continued its unstoppable growth in Europe, establishing bases of operations mainly at secondary airports and opening numerous point-to-point routes. By 2003, it was already operating 127 different routes, and a year later, it had 11 bases spread across the continent. Its expansion strategy has remained the same ever since: operating a point-to-point route network, acquiring new aircraft, maintaining a young fleet to minimize maintenance costs, operating many routes out of secondary airports, and taking advantage of incentives offered by local governments.

Many other LCCs appeared in during the 1990’s and 2000’s, including JetBlue and Frontier in the United States, Air Asia and Jetstar in the Asia-Pacific region, flydubai and flyadeal in the Middle East, and Gol and Volaris in Latin America, to name a few.

In order to understand the LCC phenomenon, we’ll start with an explanation of what defines a low-cost airline, at least at its beginnings. As their name suggests, these are airlines that offer flights at lower prices, making them accessible to a larger segment of the public.

The LCC model is based on a simple structure and very specific operating practices, mainly based on three fundamental principles:

- High asset utilization and operational efficiency: LCCs achieved high asset utilization by standardizing their fleets, which generally consisted of a single aircraft model configured with high-density seating. This facilitated crew training, reduced the logistical complexity of maintenance, and generated some economies of scale in the purchase of spare parts and equipment. In addition, their aircraft operated a greater number of daily flights, relying on short routes, secondary airports, and minimal turnaround times between flights.

- Direct distribution: Tickets were sold without intermediaries, mainly through the airlines' own channels, such as their websites or, in the early years, by telephone. This system reduced costs by eliminating third-party distribution costs and dependence on travel agencies.

- Lower labor costs: It was common for staff to be made up of non-unionized employees with lower salaries, which contributed to a more efficient operating cost structure. In addition, many employees performed multiple functions within the airline's structure, reducing staffing needs and, even more so, costs.

Another of their distinctive strategies is the operation of point-to-point routes, generally short or medium-haul, avoiding stopovers and prioritizing operational efficiency. In many cases, these routes are developed from secondary airports, where airlines can benefit from lower operating costs and even incentives or subsidies offered by local or regional authorities.

In short, all these strategies are aimed at operating with the lowest possible unit costs (cost per available seat kilometer -ASK-). During the early years, the operating model was more or less the same across different LCCs, and clearly distinct of legacy carriers, whose model at the time was dominated by indirect distribution, a full complement of services bundled in the fare (baggage allowances, seat selection, meals, etc.), and hub-and-spoke route networks.

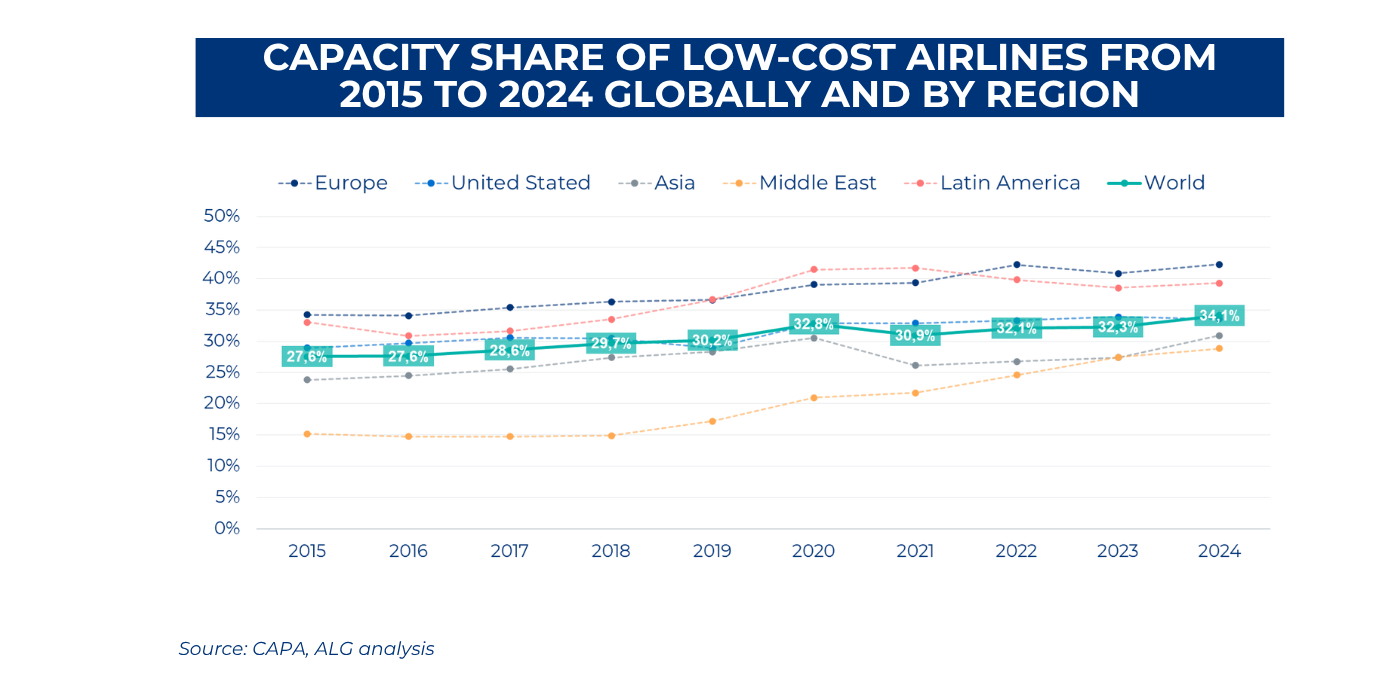

As the market evolved, LCCs gained penetration and consolidated their position to become strong players throughout the world. With about 15% of global seat capacity in the 2000’s, LCCs have seen sustained growth, more than doubling their share and consolidating an increasingly competitive position with 34.1% of the seat capacity in 2024.

This global trend has been replicated in various regions around the world. It reached its peak in Europe, the market with the highest penetration of low-cost airlines. Over the last decade, the LCC segment in this region has grown at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.4% between 2015 and 2024, rising from 34.2% of total seat capacity in 2015 to 42.3% in 2024.

For its part, the Middle East has become the most notable case of recent expansion. From 2015 to 2024, the compound annual growth rate of the low-cost share was 7.4%. However, analyzing the most recent period since 2018, the CAGR rises to 11.6%. This means that, in the last five years, the growth of LCCs in the region has been more than four times higher than the global average, reflecting a structural transformation of the region's aviation market.

In the other regions, although growth has also been positive, the pace has been more moderate. In the United States, the share of LCCs increased at an annual rate of 1.7% over the last decade, while in Asia it increased at 2.9%, which, although higher than global growth, saw a 4.5% loss in market share following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Latin America, on the other hand, is a somewhat more peculiar case. From 2020 to 2021, the region had the highest LCC share, reaching its highest point at 41.7% in 2021. After the pandemic, LCCs began to lose some market share. In 2024, they offered 39.3% of the region's seats.

As the initial rapid-growth phase leveled off, LCCs began to introduce more flexibility to their business models increase revenues and reach a wider audience. At the same time, legacy airlines also adapted their offer to make it more appealing to the large price-conscious segment of the market.

LCCs, initially focused on offering the cheapest possible flights with a single product and no fare distinctions between passengers, have evolved towards a more segmented model. Today, it is common for these airlines to offer additional “premium” services at an extra cost, such as extra-legroom seats, and even distributing fares through travel agencies. In addition, there are many instances of LCCs increasing their presence at major airports, foregoing ultra-low fares in exchange for greater visibility and access to larger markets.

For their part, traditional airlines have been forced to adopt practices typical of LCCs to protect their market share in the face of aggressive competition from them. These measures include the introduction of “basic” economy fares, the unbundling of services previously included in the ticket price, such as seat selection, baggage allowances, and meals, and even the creation of their own low-cost subsidiaries. Notable examples of these include Lufthansa's Eurowings and Iberia's LEVEL or Iberia Express, all of which were created to compete in the low-cost segment without compromising the operation of their traditional airlines.

So, while the philosophy and core business model of LCCs and legacy airlines remain distinct, there is a significant degree of convergence of key elements of the former and latter’s offerings: LCCs have introduced elements to improve and differentiate their product, while FSCs have adopted practices to adapt to an increasingly competitive market.

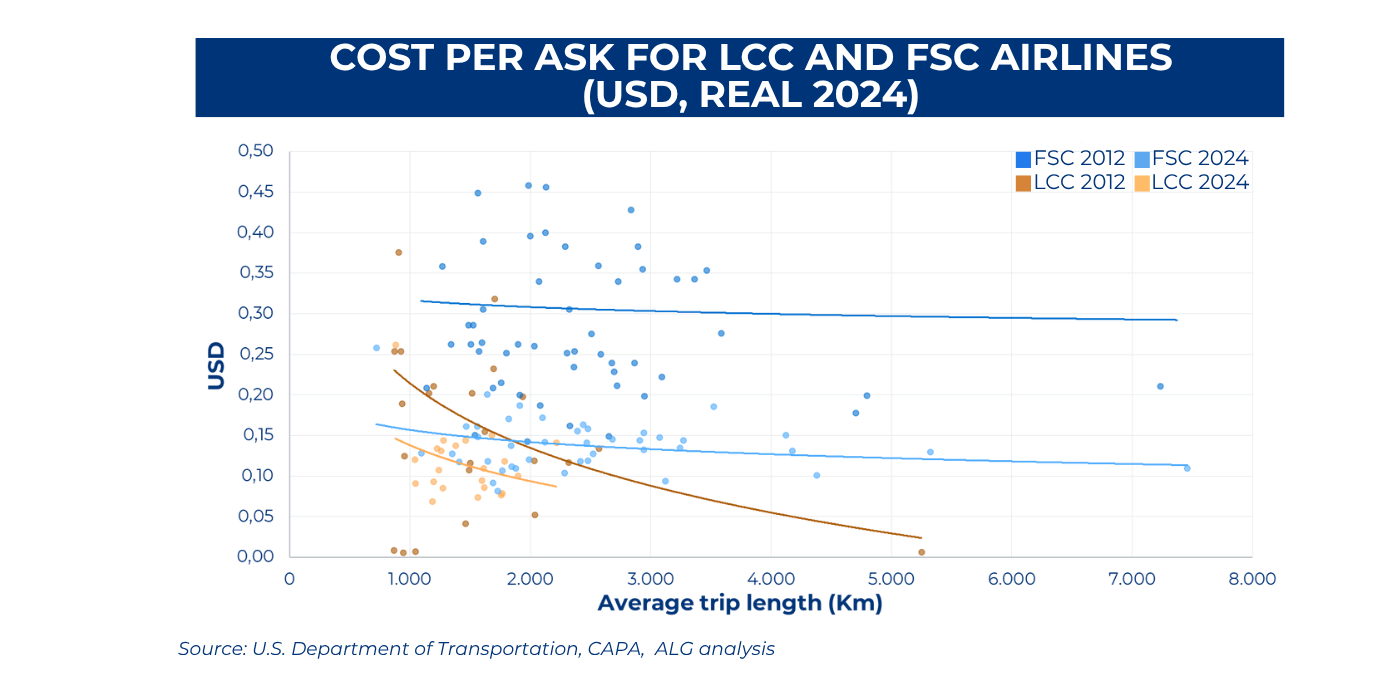

The evolution (and to a degree, convergence) of the LCC’s and legacy airlines’ business models is reflected in the evolution of the cost structures of the LCCs and legacy airlines.

Overall, unit costs for legacy airlines appear to be less impacted by average trip length than for LCCs. The reduction in CASK for legacy airlines between 2012 and 2024 is significant and can be at least partly attributed to the adaptation of their business models (increase in direct distribution, elimination of meals on short-haul flights, etc.). This behavior suggests notable advances in operational efficiency. Even so, their unit costs remain above LCC levels.

In the case of LCCs, in 2012, they already started from a significantly lower CASK: around USD 0.15 per seat-kilometer on routes of around 2,000 km, compared to approximately USD 0.30 for FSCs. By 2024, LCCs further reduced their costs, reflecting continuous improvement in their efficiency. In addition, the CASK curve has flattened compared to 2012, indicating an expansion into longer-range routes supported by new-generation aircraft.

Despite the differences in the shape of the unit cost curves for LCC and legacy airlines, and the fact that both groups improved their performance between 2012 and 2024, it is evident that the gap between LCCs and legacy airlines is significantly smaller today than it was over a decade ago. The narrowing of the gap results from a process in which legacy carriers worked very hard to eke out operational efficiencies through the commoditization of part of the cabin, while maintaining a differentiated product for frequent flyers. LCCs, on the other hand, also improved unit costs, albeit at a slower pace, given that they already started from significantly lower levels, and also because they added some complexity to their business models to make it more appealing to wider audiences.

As they continue to evolve, the business models of LCCs and full-service airlines are likely to see further elements of convergence in areas related to strategy, product, or distribution. This is likely to further narrow the unit cost gap between the two business models. This doesn’t mean, however, that the distinction between low-cost and full-service airlines will blur to the point that both business models will be indistinguishable in the future. And while the future will likely bring even more examples of LCCs adopting features that were once the exclusive domain of full-service airlines (and vice-versa), the sheer size of the travel market will support the budget, luxury, and other models in between.